One of the largest problems in current cryptocurrency implementations is the issue of slow confirmation time. The average amount of time that it takes for a Bitcoin transaction to get into a block is about 10 minutes; in practice, due to how the math works out, on average if you send a transaction and your client says "0 confirmations" you actually have about a 63.2% chance of having at least one confirmation within that time. Sometimes, you get unlucky; there have been recorded instances of there being over an hour between blocks.

To solve the problem, we have attempted to move to a faster block time, targeting one block every 12 seconds. This has several advantages: transactions get included into the blockchain much faster, so users do not need to wait for as long before seeing their transactions confirmed, and indeed the variance is much lower as well. Additionally, because each block's influence on the chain in terms of security is lower, we can also reduce the number of confirmations needed, and thus the confirmation time for higher value transactions as well.

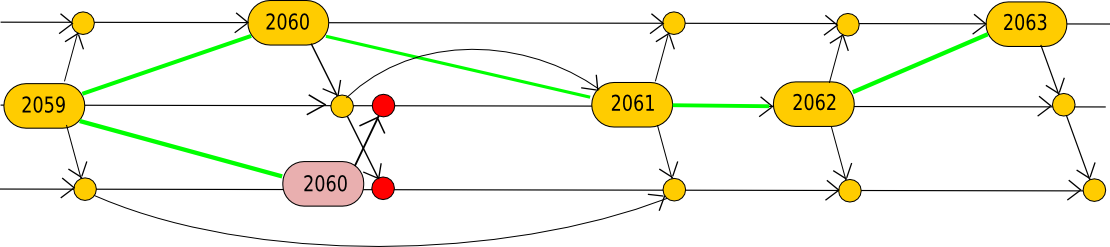

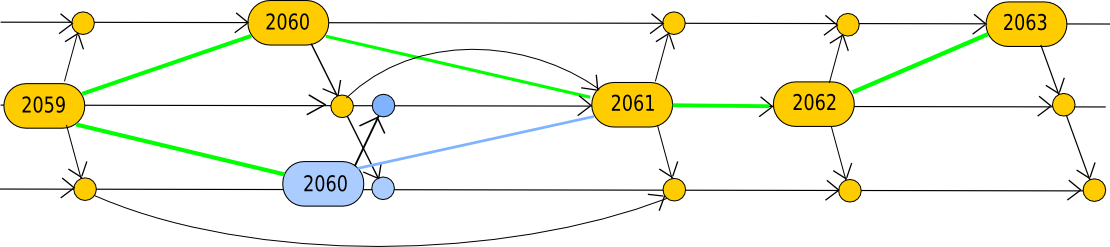

However, there is a problem with simply decreasing the block time: if blocks are being produced every 12 seconds, and it takes 12 seconds for a block to fully propagate through the network, then by the time the average miner hears about a new block another block has already been published. What ends up happening is that, with a simple protocol, every block that gets published has about a 50% chance of becoming "stale" – that is, some other block gets published at the same time, one of them becomes part of the main chain and one does not, and the one that does not is forgotten.

Why Stales are Bad

Stale rates are bad for two reasons:

- They reduce the security of the network. Intuitively, if half of all blocks are being wasted, then an attacker only needs to match the other half; hence, an attacker does not actually need 50.001% of the network in order to launch a 51% attack; rather, even in the base case an attacker with 25.002% of the network can start to do damage by wasting the resources of the rest. Bitcoin currently has a stale rate of about 1.7%.

- They harm decentralization. In a simple "winner takes all" model, if you are a small miner then someone else produced the latest block most of the time, but if you are a large miner then there's a higher probability that you were the one that created the latest block. Hence, if you are a large miner then you have an efficiency advantage: you don't need to waste the few seconds of time listening to and verifying someone else's block, since you have your own that you've already verified to mine on top of. This effect is captured by the formula:

In this formula, S(p) is how much a miner with hashpower share p earns as a percentage of their "fair share", T is the average block interval, t is the average network propagation delay and U is the uncle rate. At 60 second block times and 12 second propagation, the stale rate is 16.67% (every 12 seconds, miners are working on stale blocks on average), so a miner with 30% of the network gets a 5.7% efficiency gain over a miner with 0.1% of the network – a small, but nevertheless problematic effect.

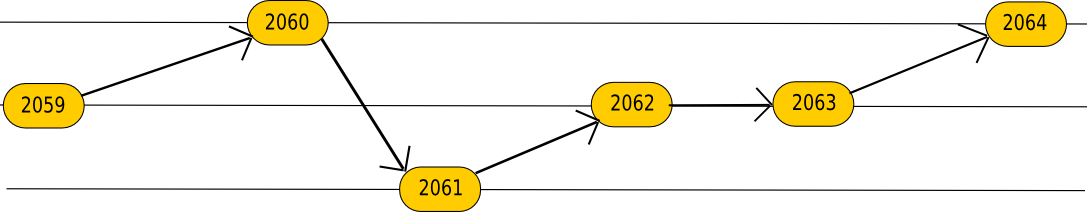

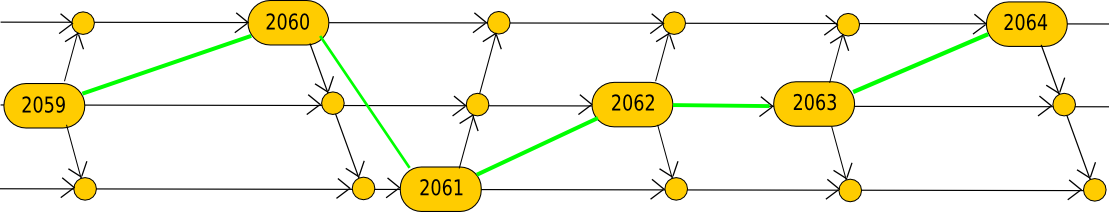

GHOST

Our solution is an extension of the GHOST protocol. The basic idea of GHOST is that, instead of just looking at a block's main-chain ancestors, the scoring function for determining the head of the chain also includes the block's "uncles" – blocks that are not in the main chain but nevertheless point to one of the block's ancestors. In Ethereum, uncles are blocks that share a grandparent with one of the block's ancestors, and blocks can include up to two uncles.

The way that rewards work is that a block which is included as an uncle receives 15/16 of a block reward (the value of this reward will be set in a later post); additionally, the block which includes an uncle gets an extra 1/32 of a block reward as a "nephew bonus". Transaction fees are not given to uncle blocks.

We have chosen a block time target of 12 seconds because we want blocks to propagate through the entire network in a small amount of time, and at the same time we don't want to create a network which is too bandwidth-intensive. The efficiency of our GHOST implementation is:

Which works out to 92.7% efficiency at a 12-second target (which, with stales included, ends up being a realized block time of about 22 seconds).

Uncles

An uncle in Ethereum is defined as follows:

- It must be a direct child of the kth generation ancestor of the block in question, where 2 <= k <= 5

- It cannot be an ancestor of the block in question

- It must have a valid block header

- It must not have been included as an uncle in a previous block

The reason for the range 2 <= k <= 5 is that the network needs some time for uncles to propagate; it may take a few seconds before a block is published by its creator, and an additional few seconds for all the references to it to propagate. On the other hand, the reason why k <= 5 is that we need to set some limit; otherwise, uncles may end up dating back to the genesis block and the algorithm becomes extremely cumbersome.

Here is some math. At t = 12, with 25% mining power, and with a target block time of 12 seconds:

- Expected blocks per time unit: 1/12

- Probability that one block comes from a particular set: 0.25

- Expected uncle revenue per time unit: 0.25 * (1 - 0.25) * 1/12 * 15/16 = 0.01465

- Expected nephew revenue per time unit: 0.25 * (1 - 0.25) * 1/12 * 1/32 = 0.000488

- Total revenue per time unit: 0.25 / 12 + 0.01465 + 0.000488 = 0.0360

- Revenue as share of "fair share": 0.0360 / 0.08333 = 0.4320 / 0.4167 = 1.025

Hence, a miner with 25% mining power gets about 2.5% more than their "fair share" of rewards. A single-level GHOST implementation actually provides a worse ratio: a large miner would benefit because, in a tie, they would be more likely to be on the winning side, and so would waste less time trying to mine on top of the losing block.

Simulations

To make sure everything works as expected, we ran simulations. In our simulations, we had 503 nodes, each with randomly chosen hashpowers, processing powers and network latencies. We then simulated thousands of blocks of activity, and compared the results to our mathematical expectations.

The expected result is an efficiency of about 92.6%, and this is what we got. Miners with 25% of the hashpower earn about 2.5% more than their fair share, and miners with 5% of the hashpower earn about 0.5% less.

Note that the purpose of GHOST is to prevent centralization pressure, and not to make the blockchain more secure against 51% attacks. GHOST provides miners with an incentive to not mine selfishly, and to actually include uncles in their blocks, because they get extra reward for it. But GHOST does not change the fact that if an attacker has >50% of the hashpower they can dominate the chain.

The block time may still be adjusted up or down somewhat based on experience; we want to make sure that the network is stable and that we're not creating excessive bandwidth load. But overall, we are confident that we have a reasonably good protocol.